Take a dive into the vault with this Wesleyan Magazine article by Scott Higgins.

I regularly return to The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) in my film courses, and so it is a delight to see the film finally available on DVD in a restoration that does some justice to its grandeur. Robin Hood provides a glimpse of classical Hollywood’s formal perfection and insight into the popular imagination of late 1930s America. Much of film’s appeal derives from the fact that it was produced by Warner Bros., the studio of hard-hitting, topical Cagney gangster pictures and Busby Berkley musicals. Robin Hood, one of Warner’s few costume prestige-pictures, and only its third Technicolor production, was a departure. It cost the studio an unprecedented $2 million, but it moves with the speed of an inexpensive B film. Prince John (Claude Rains) announces his villainous coup with the simple declaration, “I’ve kicked Longchamps out! From now on I am Regent of England.” Moments later, Robin (Errol Flynn) storms into the hall, lays a deer’s carcass at John’s table, and announces “From this night on I use every means in my power to fight you.” Prince John attacks, Robin escapes and, amid a hail of arrows, Maid Marian (Olivia de Havilland) flashes a concerned glance. In trademark Warner’s fashion, the game is on with a minimum of fuss.

The narrative compression helps bring the genre’s politics sharply forward. The adventure genre has always envisioned a world where people are judged by their abilities rather than class, and where determined individuals can change government for the better. In Robin Hood these ideals forcefully resonate with 1930s concerns. According to the film’s rhetoric, a just government, in Robin’s Sherwood or in the late-1930’s America, should not squander resources on the rich, nor on international affairs. When the good King Richard returns to Sherwood, Robin chides the leader “whose job was here at home protecting his people instead of deserting them to fight in foreign lands.” Though topical, the film never slackens the pace to deepen characters or advocate an agenda. Instead, again in the Warner Bros. style, Robin Hood does everything at once. Distinctions between romance and politics collapse when Robin tenderly declares to Marian, “Normans or Saxons, what’s that matter? It’s injustice I hate.” Produced in the late Depression and, eerily, at the bring of the war against Fascism, Robin Hood is oddly relevant without betraying the genre’s escapist roots.

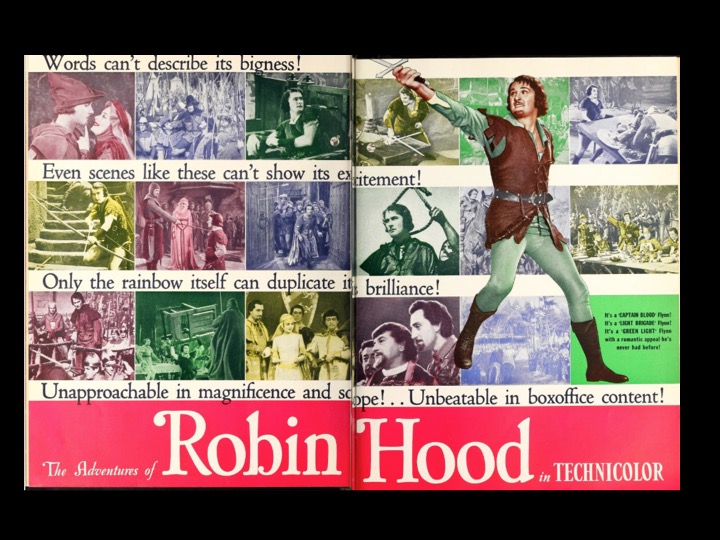

Robin Hood is also an aesthetic milestone in Technicolor design. Introduced in 1934, “three-strip,” Technicolor was a complicated and expensive system that used three negatives to create a full-color image. Technicolor films were painstakingly designed works of art. The Technicolor Corporation, in concert with the major studios, developed “color scores,” planning a film’s palette around the drama, much like a composer might create a musical score. Where earlier films had subdued Technicolor to make it an unobtrusive adjunct to the story, Robin Hood gleefully puts a broad gamut of red, yellow, green, violet, and blue on brilliant display. Like a musical, it weaves in big “production numbers,” like the dizzying archery contest, that dazzle with an intensity that must have overwhelmed viewers raised on black-and-white.

At its best, Technicolor filmmaking was the art of a million details, and it is in the dense texture of its costumes and mise-en-scene that Robin Hood distinguishes itself. When Sir Guy of Gisbourne (Basil Rathbone) is introduced in the cold hall of Prince John’s palace, his back is to the camera so that his rich blue cape contrasts with deep velvety red accents stretched across the composition; he is set like a blue sapphire in a band of rubies. Suddenly, Sir Guy turns, the gold lining of his cape flares, and he reveals the brilliant yellow emblem on his chest. The flourish is only momentary, but it completes a visually arresting primary triad of blue, yellow, and red. Technicolor boldly punctuates our first glimpse of Robin’s arch rival.

After countless viewings, Robin Hood still astonishes with its deft mosaic of color. If the care lavished on the film seems inordinate for a simple adventure yarn, it also reminds us of the strength of the Hollywood industry and its importance to American culture in the studio era. With each return to Sherwood we relive the basic pleasures of innocent adventure, but the journey also affords fresh discoveries.