The CFILM podcast is back! Jane Goldenring talks about her experience as a producer and how film and TV have changed over the years.

Month: June 2018

Coming Soon… Michael Slowik’s Fall Course Offerings

By Michael Slowik

This fall, I will be teaching two courses that—on the surface—may seem to have little to do with each other. Both, however, are fundamentally engaged with analyzing and understanding the power and potential of cinema. The first class—on the Western—approaches the genre from the perspective of craft, directorial vision, and cultural mythology. Tracing the genre from its earliest iterations through Django Unchained and beyond, we ask: what are the character types and plot structures commonly found in the genre? How do iconic images—and sounds—impact the audience? How has the genre served as a way for particular directors—including Howard Hawks (Red River), Budd Boetticher (Seven Men From Now), Sergio Leone (A Fistful of Dollars), and of course John Ford (Stagecoach, The Searchers)—to make their own personal statements? And since so many Westerns are fundamentally about the myths of America as a country, how have these myths been employed to reflect upon—and make statements about—the nation’s identity? The course is a mostly chronological history of the Western, which gives us the opportunity to consider how elements of the genre change over time. It is illuminating, for instance, to consider how a more noble conception of the gunfighter character in The Gunfighter or Shane becomes the more fallible protagonist of a “revisionist” Western like The Wild Bunch or McCabe & Mrs. Miller.

If the Western class deals with filmmaking within a broad American mythological landscape, my other course (titled “Cinema Stylists”) is more far more personal in orientation. This course centers on a close examination of four directors—Josef von Sternberg, Max Ophuls, Douglas Sirk, and Federico Fellini—who have stamped their personal vision on their films by putting film style front and center. All four filmmakers had unique visions, and figured out various ways to use cinema for their particular concerns. Obsessions mark the work of all four directors: von Sternberg collaborated with the actress Marlene Dietrich seven times in the early 1930s (including The Blue Angel, Morocco, Blonde Venus, and The Scarlet Empress), Ophuls’ films often feature exceptionally formal, rigorous and even circular plotting (such as in La Ronde and The Earrings of Madame de…), Sirk obsessively returned to stylistically elaborate Hollywood melodrama (in movies like the aptly titled Magnificent Obsession), and Fellini found himself increasingly preoccupied with his own personal fantasies and dreams (such as 8 ½). Students will submerge themselves in highly personal worlds of masks, performances, illusions, and decorated images, and will hopefully emerge with a better understanding of how cinematic stylization can engage with reality and suit a director’s personal vision.

The Nitrate Picture Show

By Michael Slowik

In early May, I had the pleasure of attending The Nitrate Picture Show at the George Eastman House in Rochester, NY with my colleagues Jeanine Basinger and Marc Longenecker. The nitrate festival is—to my knowledge—unique in the sense that it is the only festival to screen exclusively nitrate prints. As film historians know, nitrate was the film stock used around the world until about 1952, when a switch to acetate film stock occurred. Nitrate is known for being both highly flammable and prone to deterioration over time, so it is truly a rare privilege to be able to view high-quality nitrate prints in 2018.

So, did the festival’s films look different from the digital images that we call still call “film” today? In a word: YES!! From the first film to the last, the nitrate prints offered a noticeably greater depth of field—along with a sense of crispness between various objects in the frame—that even the best digital projections today cannot match. And in terms of gradation, I was regularly struck by the astonishing array of gray tones available on a nitrate print. These subtle gradations allow the image to convey textures, shapes, and other subtleties that we simply no longer experience in today’s digital cinema.

Every film on the program—whether short or feature-length, black-and-white or color—was a treat to watch on nitrate, but for me, some of the greatest pleasures included two Technicolor films: a short Movietone travelogue called Along the Rainbow Trail and Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Red Shoes. Though colored film stock deteriorates over time, both films—and especially The Red Shoes—were still able to suggest the stunning level of color saturation that nitrate Technicolor could provide. I also greatly enjoyed Anthony Mann’s Winchester ’73—probably the best film on the program—for the way in which nitrate integrated character with landscape, especially the climactic shootout on the high rocks of Arizona. But for me, the nitrate highlight was The Razor’s Edge, a superbly shot 145-minute evocation of beauty and loss that I had viewed many times, but never on a nitrate print. Using lavish, carefully lit images and well choreographed staging and blocking, The Razor’s Edge absorbs you in the beauty of post-World War I high society (not the mention the beauty of Tyrone Power and Gene Tierney in their prime), while simultaneously giving you the sense that—through mistakes, missed opportunities and tragedies—it is a world that is gone and will never return. Only via gorgeous nitrate can The Razor’s Edge fully evoke these qualities.

The Razor’s Edge

The nitrate festival is an invaluable resource for putting historians and movie buffs in the shoes of audience members of the past. Watching these films in their original format helps us understand why film dominated popular entertainment for so long, and why so many people in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s fell in love with, obsessed about, and habitually returned to the movies.

The CFILM PODCAST! Episode FIVE! With Katie WALSH!

In this episode, we sit down with Katie Walsh, film critic at the LA Times (among others!). We talk about reviewing seven movies a week, whether Rotten Tomatoes has ruined film, and the astonishing revelation that there are Twitter nerds going to bat for Justice League.

Limitations of Life: Fassbinder Learns from Sirk

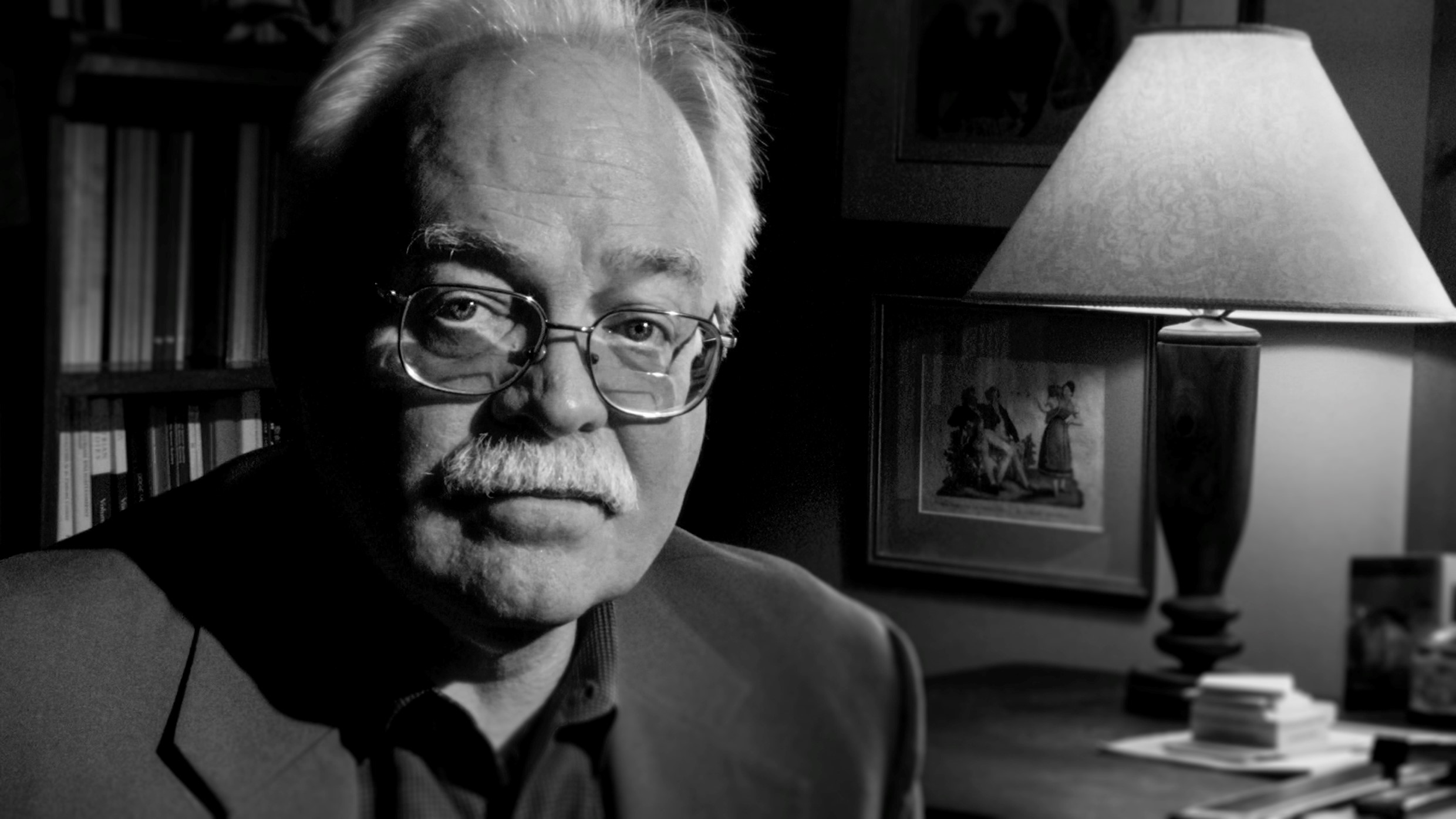

By Leo Lensing

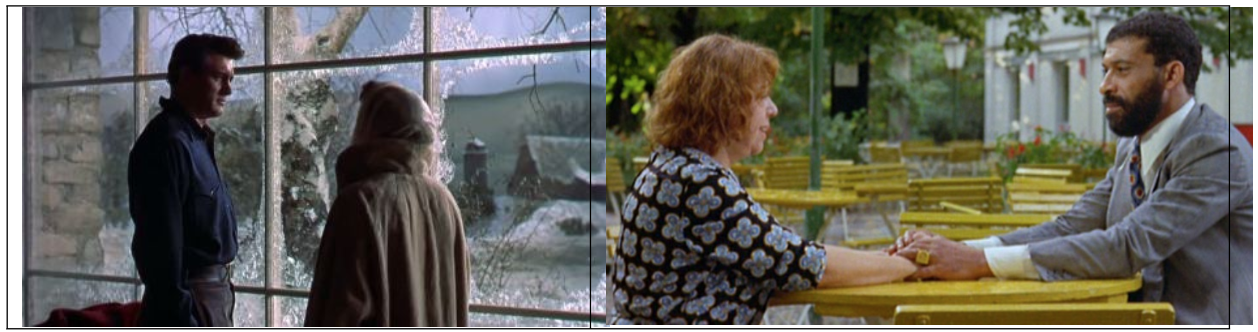

As students of “New German Cinema” know, I show sequences from Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955) when we discuss Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s bold adaptation from 1973, Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. Fassbinder substitutes a more complicated relationship between a younger Moroccan immigrant worker and an older German cleaning lady for the 1950s version of a fraught May-December romance embodied in technicolor (and lily white) by Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman.

I have threatened for years now to repeat a seminar that I taught once long ago, “Limitations of Life: Fassbinder & Sirk,” and this fall I will make good on that underhanded promise with a course that explores the relationship between the once neglected German-American émigré director and the enfant terrible of the New German Cinema. Fassbinder’s 1971 essay “Imitation of Life. Six Films by Douglas Sirk” was a major factor in the critical rediscovery of Sirk’s subversive melodramas. The encounter with these films accelerated Fassbinder’s ambition to make films that combined Brechtian “distanciation” with Hollywood glamor. The course will explore the connections between the Sirk films that Fassbinder first saw in Munich in 1971, including Written on the Wind and Imitation of Life, and his early Sirk-inspired social dramas of contemporary German life as well as their impact on the great historical trilogy about the early postwar years, The Marriage of Maria Braun, Lola, and Veronica Voss (1978-1981). We will also look at two films Sirk made in Germany in the late 1930s with Zarah Leander, the Swedish-born star of German cinema in the early years of Nazi Germany. These films, too, marked Fassbinder’s work and are perhaps one of the inspirations for Lili Marleen, his portrait of a torch singer compromised by her performances for the “culture industry” of the Third Reich.

As students of all my film courses know, I like to show them what dealers in movie memorabilia call the “paper” of the industry: posters, programs, postcards, scripts, even letters and other manuscripts and typescripts. During the March break – in a bookstore in Berlin piled high with cinema odds and ends of all kinds – I found this picture-postcard portrait of Zarah Leander from the 1940s:

In The Marriage of Maria Braun, Fassbinder has the heroine and her sister Betti making their way through the ruins of their bombed out high school before singing “Nur nicht aus Liebe weinen” (Never Cry Over Love), a hit song from one of Leander’s early films and a kind of anthem of their adolescence.

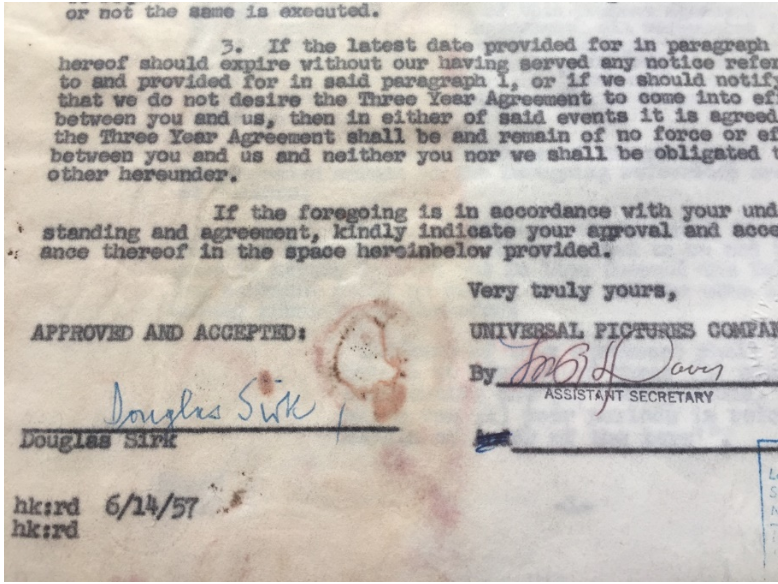

Not long before Sirk made Imitation of Life, he signed a 24-page-plus contract with Universal Studios, which I rescued from a book dealer in Baltimore.

Sirk agreed to “render his services as a motion picture producer, including, but not limited to, services in supervising photoplays and/or services in a consulting capacity with respect to photoplays including the selection, writing, and development of stories, adaptations, dialogue and/or continuities, cutting, editing and the selection of cast and all the services as may be required of producers according to the custom of the industry.” In other words, Universal wanted it all! Sirk was also required “to conduct himself with due regard to public conventions and morals and to agree that he will not do or commit any act or thing that will degrade him in society or bring him into public hatred, contempt, scorn or ridicule or that will shock, insult or offend the community or ridicule public morals or decency.” It’s safe to say that this might have worked for Sirk – it was the 1950s after all – but never for Fassbinder.

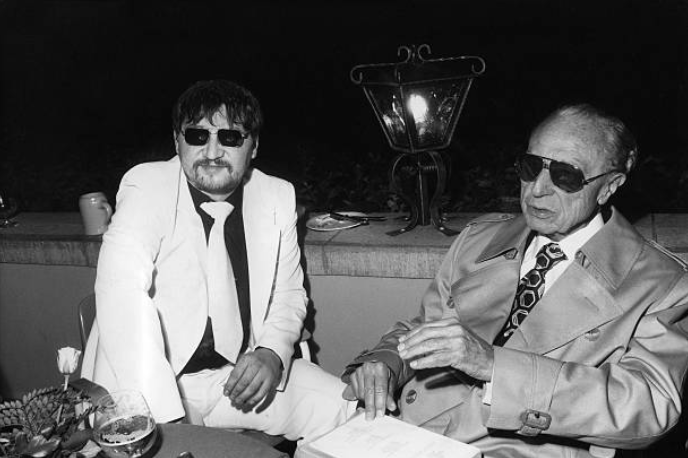

Commentators on the relationship between Fassbinder and Sirk rarely mention that not only did the young filmmaker eventually meet Sirk and participate in a joint interview, they also made a film together. Juliane Lorenz, the editor of Fassbinder’s last films and the president of the Fassbinder Foundation, has given me a private DVD copy of Bourbon Street Blues, a short based on a story by Tennessee Williams. This scarcely known, rarely shown film will be another object of the course’s inquiry into one of the most productive intergenerational relationships in the film history of the twentieth century.

LIMITATIONS OF LIFE: Coming in September 2018!

What and WHY will we teach in the Fall?

The echoes of commencement weekend have faded, and we are busy balancing budgets, repairing equipment, cleaning our desks, watching probably too much FilmStruck, and getting ready to start all over again. This is the time of year that a teacher can honestly ask questions like “what will I teach” and “why will I teach it?” In the heat of the semester we rarely have time for reflection, so I’m asking my colleagues to share their thoughts on this blog over the summer. For my part, on Tuesday September 5th at exactly 8:50 am, I’ll be in the Goldsmith Family Cinema launching our gateway class FILM 307: The Language of Hollywood. This is our introduction to Wesleyan Film, and so I’ll be meeting many members of the class of 2022 as well as students from across the campus who are intrigued by film. It is a “film watching” class, but (not so) secretly it is also a filmmaking class. In it, we aim to understand films from the perspective of the filmmaker, to reverse-engineer cinema to see how it all works. CFilm’s curriculum is built on the premise that study and practice are inseparable and mutually beneficial. Film critics and historians have a LOT to learn from the experience of holding a camera, setting up lights, and cutting together pieces of stock. For filmmakers, there’s no better way to open up the craft, broaden visual vocabularies, and find inspiration than sitting in the dark, watching, thinking, and feeling.

Because I’m a historian, and because “watching, thinking, and feeling” doesn’t quite work as a syllabus, I organize this class historically. We look at three changes in film technology: the coming of sound, the introduction of color, the shift to widescreen, and the development of 3D. The class isn’t so concerned with the history of technology (if you want to know, say, about the history of Technicolor, I have a book for you), but with how working filmmakers react when change happens.

On that first day, I will probably show one of the great silent films from the 1920s. For the past several years I’ve started with Frank Borzage’s ravishing romance Street Angel, a movie so confident in its storytelling that the absence of synchronized dialogue hardly seems a deficit. Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell find love, lose it, and then miraculously find it again in shimmering soft focus. What more could one possibly ask from cinema? And yet, within just over a year no studio in Hollywood was making silent films! The transition to sound was a crisis point for all film artists. They lost some tools, gained others, and struggled to find the same emotional power and visual poignance in the new era of “talkies.” Looking at what filmmakers do under pressure, at how they solve problems when the game has changed, reveals how artists think, what they value about their medium, what works and what doesn’t. Within a short time, sound cinema had the confidence and air of effortlessness that silent film once claimed. But studying the excitement and desperation of sound when it was new helps us see its possibilities with fresh eyes (and ears). This sensitizes us to film form, so that we can look at a much later sound film like Ghost Ship, a wonderfully strange horror movie from the early 1940s, and find filmmakers who kept the novelty of sound alive, using effects, music, and silence, to create a new emotional journey.

At the end of this class, elements of film form like sound, composition, lighting, cutting, depth, and color should be visible in a new way. If class goes really well, cinema will cease being a “given” and become instead a field of possibilities, some long forgotten, ripe for exploration. Using sound in a movie should feel like a positive choice rather than a stale inevitability. Watching is the gateway to making. That’s the BIG idea behind this class, and I hope to keep it in mind even in the depths of November when we are all overwhelmed with deadlines, page-counts, and tests. For now, with summer stretched before me, I’ll be revising, re-watching, reworking, rethinking.