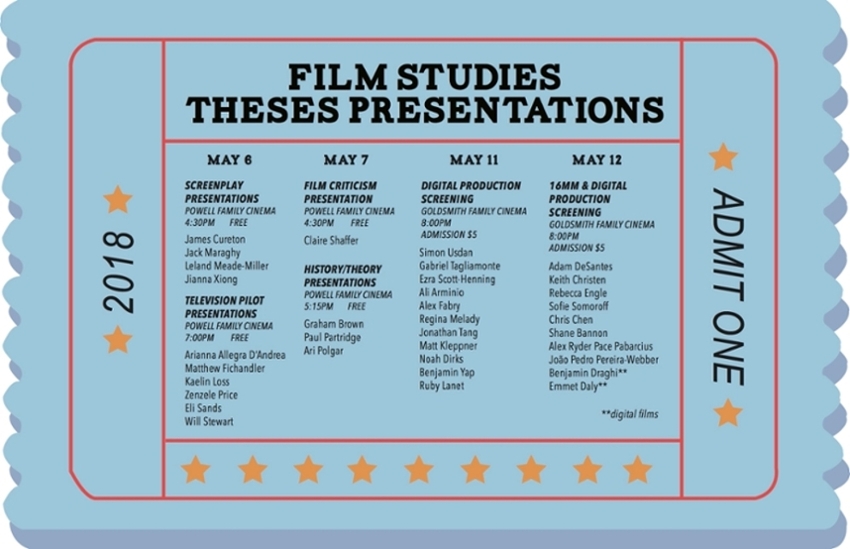

By Michael Slowik

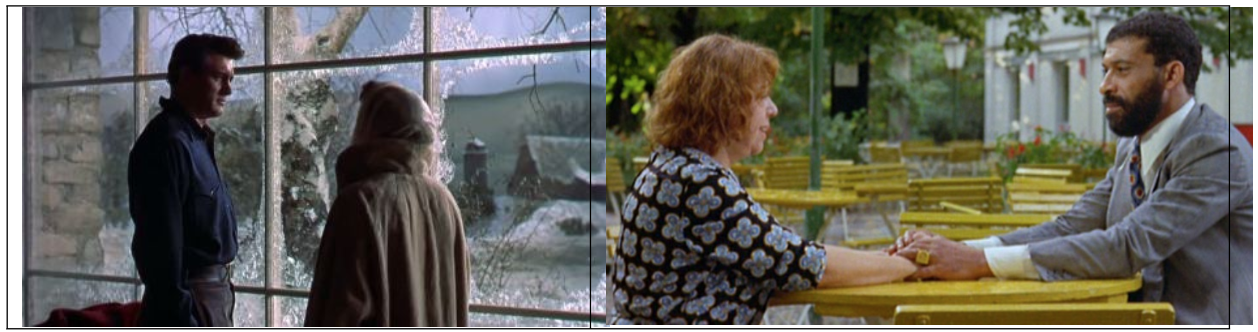

This fall, I will be teaching two courses that—on the surface—may seem to have little to do with each other. Both, however, are fundamentally engaged with analyzing and understanding the power and potential of cinema. The first class—on the Western—approaches the genre from the perspective of craft, directorial vision, and cultural mythology. Tracing the genre from its earliest iterations through Django Unchained and beyond, we ask: what are the character types and plot structures commonly found in the genre? How do iconic images—and sounds—impact the audience? How has the genre served as a way for particular directors—including Howard Hawks (Red River), Budd Boetticher (Seven Men From Now), Sergio Leone (A Fistful of Dollars), and of course John Ford (Stagecoach, The Searchers)—to make their own personal statements? And since so many Westerns are fundamentally about the myths of America as a country, how have these myths been employed to reflect upon—and make statements about—the nation’s identity? The course is a mostly chronological history of the Western, which gives us the opportunity to consider how elements of the genre change over time. It is illuminating, for instance, to consider how a more noble conception of the gunfighter character in The Gunfighter or Shane becomes the more fallible protagonist of a “revisionist” Western like The Wild Bunch or McCabe & Mrs. Miller.

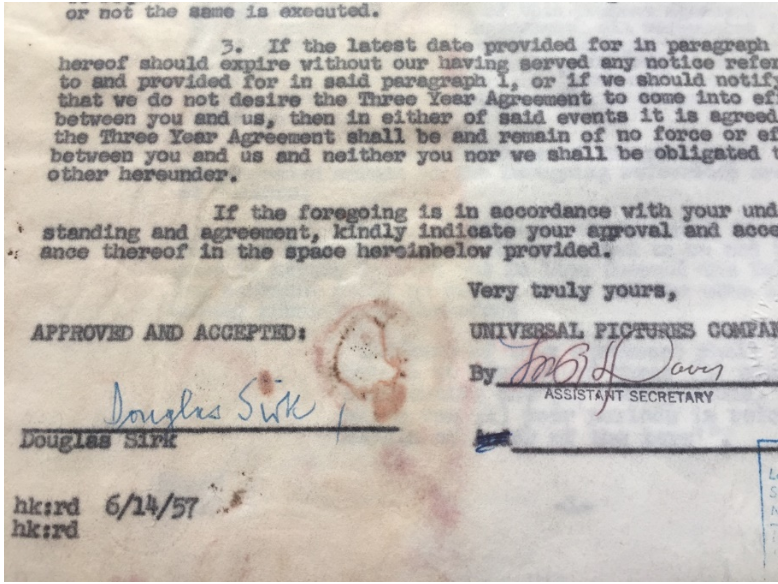

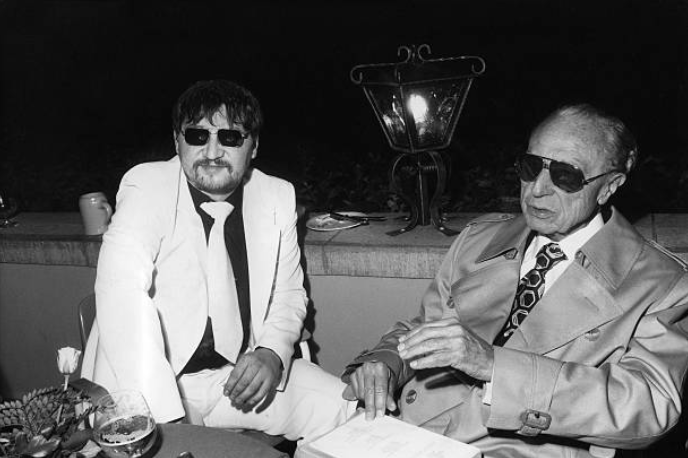

If the Western class deals with filmmaking within a broad American mythological landscape, my other course (titled “Cinema Stylists”) is more far more personal in orientation. This course centers on a close examination of four directors—Josef von Sternberg, Max Ophuls, Douglas Sirk, and Federico Fellini—who have stamped their personal vision on their films by putting film style front and center. All four filmmakers had unique visions, and figured out various ways to use cinema for their particular concerns. Obsessions mark the work of all four directors: von Sternberg collaborated with the actress Marlene Dietrich seven times in the early 1930s (including The Blue Angel, Morocco, Blonde Venus, and The Scarlet Empress), Ophuls’ films often feature exceptionally formal, rigorous and even circular plotting (such as in La Ronde and The Earrings of Madame de…), Sirk obsessively returned to stylistically elaborate Hollywood melodrama (in movies like the aptly titled Magnificent Obsession), and Fellini found himself increasingly preoccupied with his own personal fantasies and dreams (such as 8 ½). Students will submerge themselves in highly personal worlds of masks, performances, illusions, and decorated images, and will hopefully emerge with a better understanding of how cinematic stylization can engage with reality and suit a director’s personal vision.