By Ben Model

You will need both sides of your brain for the course I’ll be teaching this spring, “Silent Storytelling”. You use both anyway, but it’s that right brain of yours that is more engaged in the silent film experience. That’s more of what’s at the core of the trajectory we’ll cover.

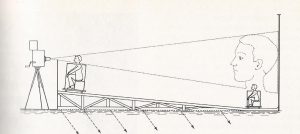

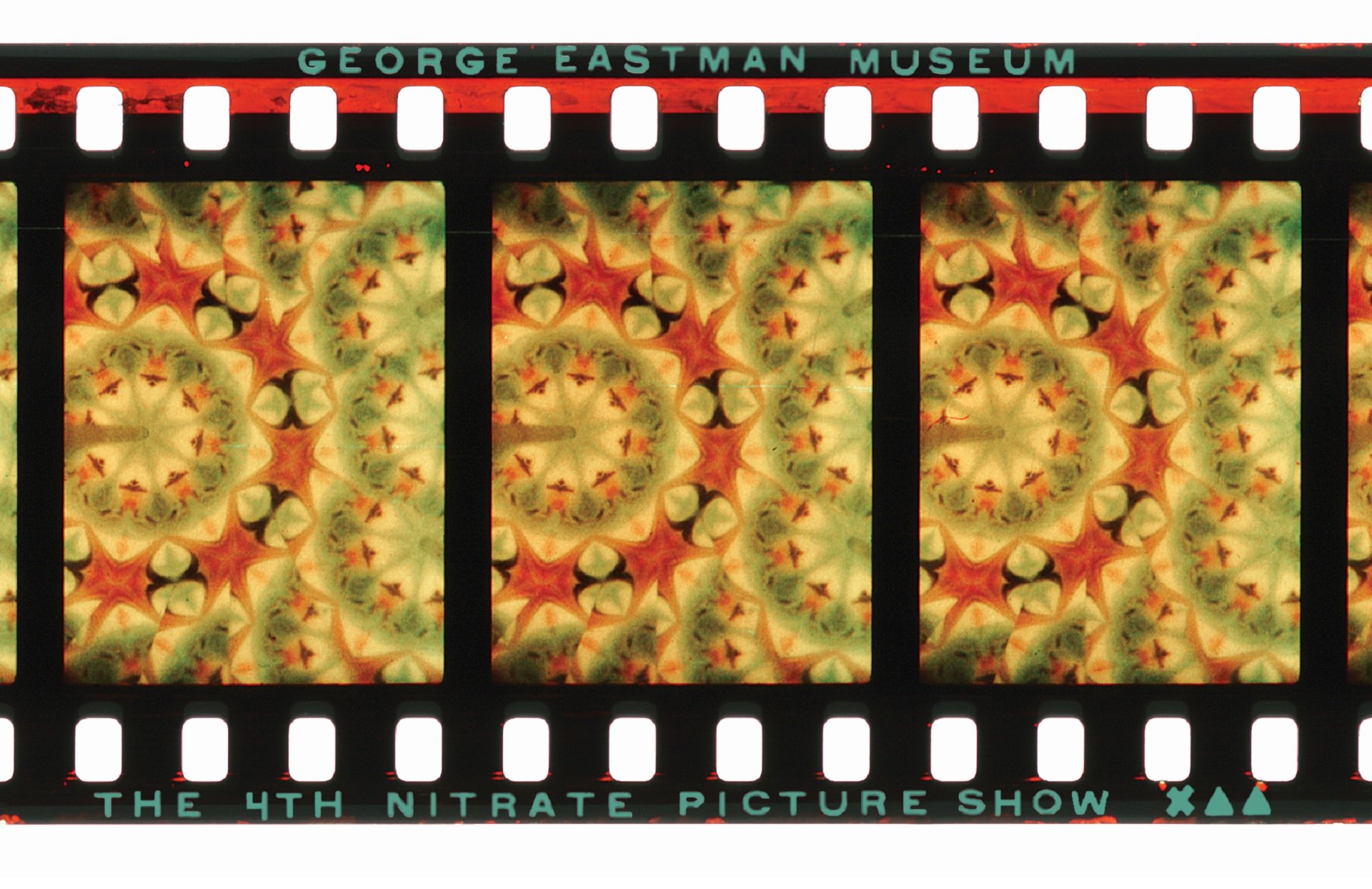

The course traces the development of film’s visual storytelling language, from the early 1910s all the way through the end of the silent era. What we’ll see, experience, and process – and with live piano accompaniment at every class! – is the gradual decrease of onscreen information being spoon-fed to the audience so that more of the storytelling is assembled out in the theater by the movie-goer.

In my work as a silent film accompanist over the last 35+ years, I go on each film’s journey right along with the audience. Silent film accompaniment is about taking in both the film and the audience. I use music to synthesize the two so that the audience is able to connect emotionally with the drama or humor of the film and engage in that pure cinema dream-state. Doing this has for thousands of films at thousands of shows made me much more aware of the language of cinema and how it’s “spoken” to and understood by an audience.

Silent film didn’t know it was missing anything at the time. Until talkies ended the medium in 1929, silent movies were just called “movies”. Silent cinema utilized every element at its disposal to tell stories, entertain, and move people, and every bit of film language was developed and used to a poetic maximum during the silent era.

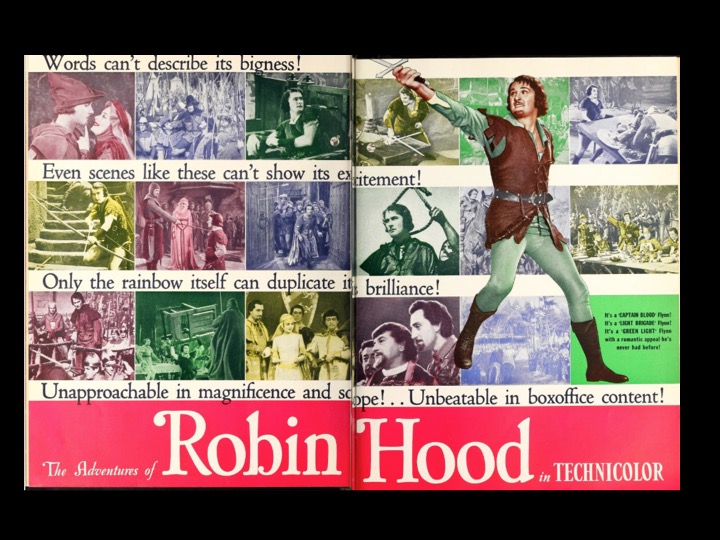

We’ll get to see how this was put into practice by many luminaries and pioneers of the era: D.W. Griffith, Lois Weber, Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Vsevelod Pudovkin, Douglas Fairbanks, Oscar Mischeaux, Buster Keaton, William S. Hart, Laurel & Hardy, Erich von Stroheim, Ernst Lubitsch, King Vidor, and more.

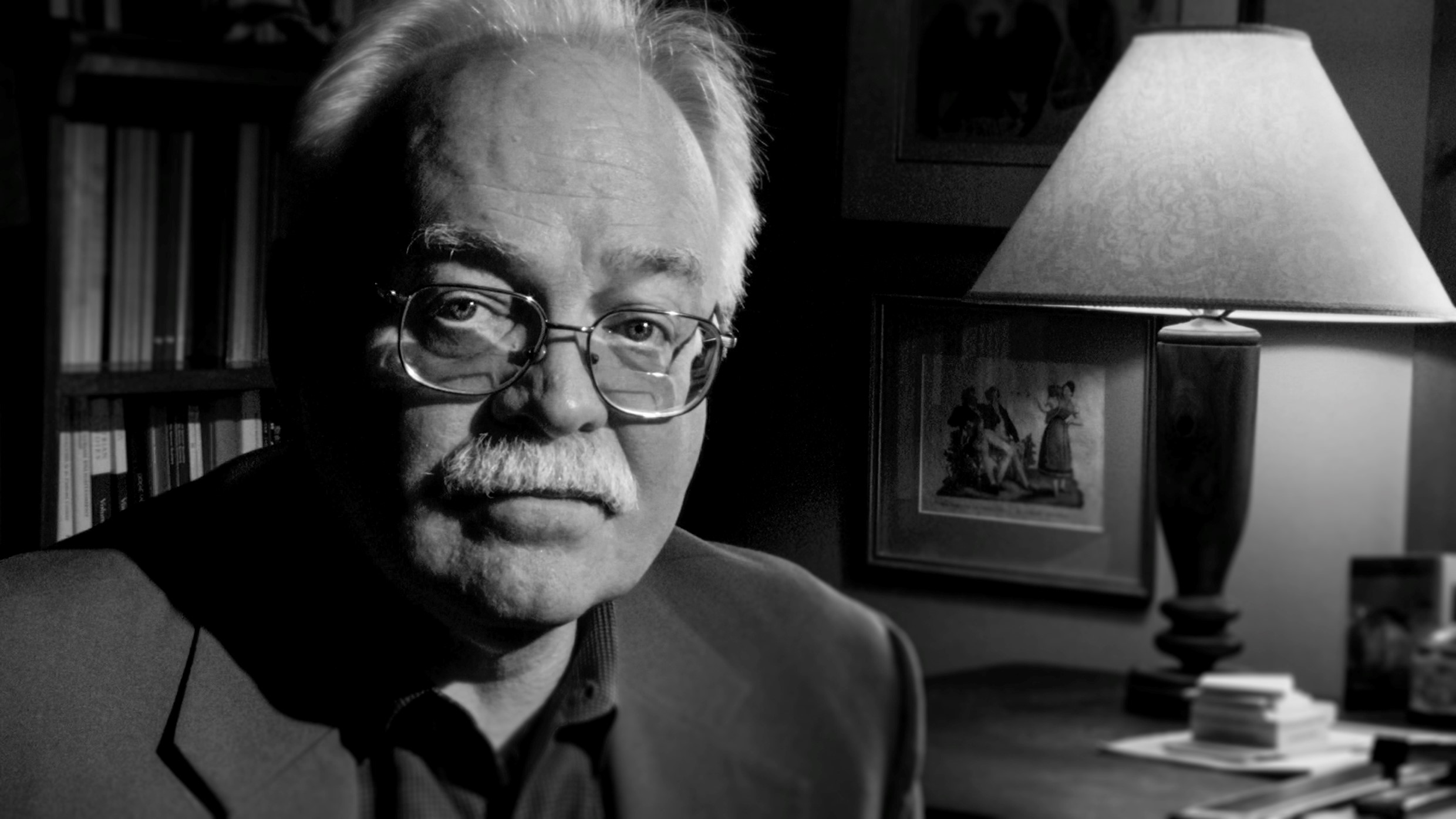

Kevin Brownlow, the Academy-Award-winning silent film historian, archivist and restorationist, wrote that with silent film, the audience is the final participant in the filmmaking process. That’s the right-brain part of silent film I was referring to. We’ll explore this during the course, right along with all that historical information and factoids that’ll go into your left-brain.

Man is an observational documentary about a very unique moment in Indian politics, the rise of the Common Man Party (Aam Aadmi Party, AAP). It documents the early years of AAP, from the party’s inception as an anti-corruption movement, to its culmination as the ruling party in the state of New Delhi. This documentary is compelling for two reasons. First, it gives the viewer a singular and insightful glimpse into a unique democratic process; the formation of a political party from the grassroots level. Second, it very effectively utilizes the observational documentary form. The filmmakers Vinay Shukla and Khushboo Ranka filmed for over 400 hours with their unobtrusive DSLR camera to then crystallize that footage into a crisp 100 min narrative. Their documentary gives the audience an uninhibited and honest look into the emergence of AAP and reveals the machinations behind the political haze. Four years hence, the AAP has lost its idealism and devolved into just another political party. This time capsule of their incredible rise is euphoric nonetheless.

Man is an observational documentary about a very unique moment in Indian politics, the rise of the Common Man Party (Aam Aadmi Party, AAP). It documents the early years of AAP, from the party’s inception as an anti-corruption movement, to its culmination as the ruling party in the state of New Delhi. This documentary is compelling for two reasons. First, it gives the viewer a singular and insightful glimpse into a unique democratic process; the formation of a political party from the grassroots level. Second, it very effectively utilizes the observational documentary form. The filmmakers Vinay Shukla and Khushboo Ranka filmed for over 400 hours with their unobtrusive DSLR camera to then crystallize that footage into a crisp 100 min narrative. Their documentary gives the audience an uninhibited and honest look into the emergence of AAP and reveals the machinations behind the political haze. Four years hence, the AAP has lost its idealism and devolved into just another political party. This time capsule of their incredible rise is euphoric nonetheless.